Pandemic Influenza Mortality Reduced by Medicaid Coverage

What role can health insurance play in ameliorating the health effects of a pandemic? In The Value of Health Insurance during a Crisis: Effects of Medicaid Implementation on Pandemic Influenza Mortality (NBER Working Paper 27120), researchers Karen Clay, Joshua A. Lewis, Edson R. Severnini, and Xiao Wang examine two historical influenza pandemics to answer this question.

The implied magnitudes of the reductions in infant mortality from Medicaid are quite large: approximately 1.4 fewer infant deaths per 1,000 live births in the severely affected counties.

Flu pandemics in 1957-58 and 1968-69 were each responsible for more than 100,000 deaths in the United States. Vaccines did little to prevent the spread of either flu, because of insufficient vaccine supplies in 1957-58 and a lack of an effective vaccine in 1968-69. Public health measures such as quarantines were not widely used to control the spread of infection during either period.

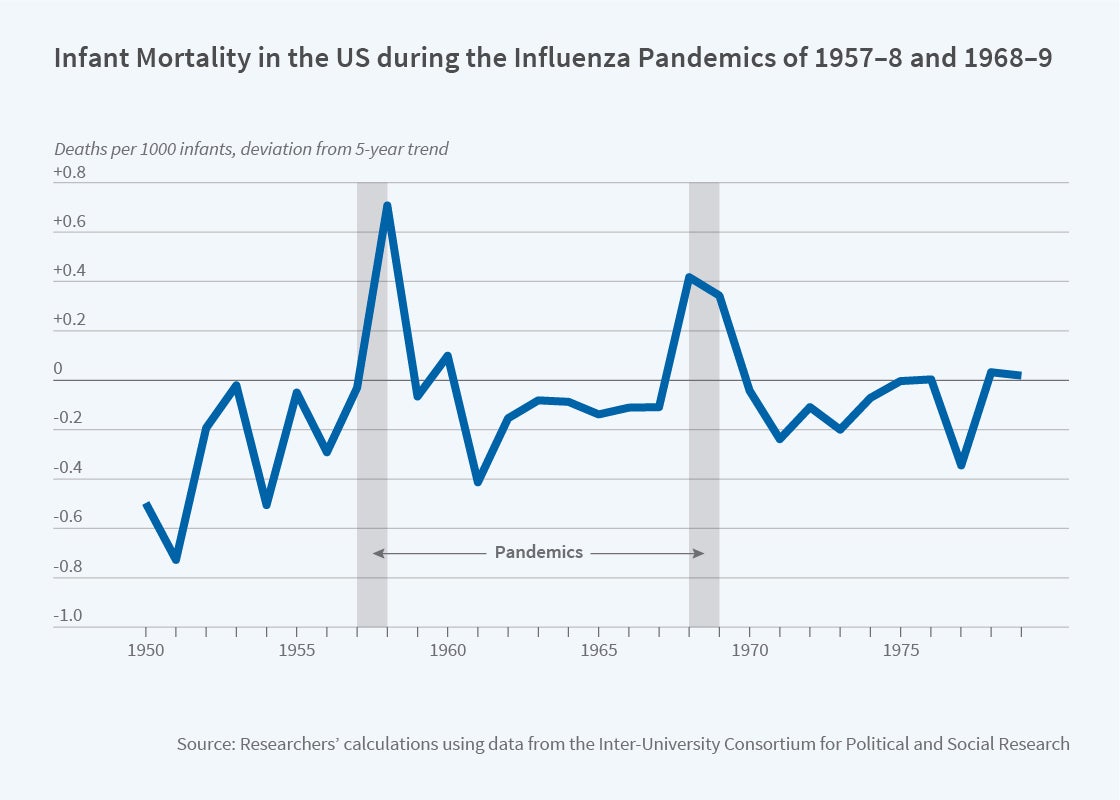

Pregnant mothers were especially vulnerable to these pandemics and, as the figure shows, infant mortality rates spiked during both flu seasons. These pandemics also disproportionately affected urban populations, due to higher transmission rates, and those exposed to air pollution from coal, due to increased susceptibility to respiratory infections and complications. For example, residing in a fully urbanized county during the 1957-58 flu was associated with approximately one additional infant death per 1,000 live births, compared to residing in a completely rural county.

A key difference between these pandemics, however, was patient access to health insurance. By 1968, when the second of the flu pandemics arrived, Medicaid had begun providing health insurance to low-income households. The program specifically targeted women and children who were recipients of federally funded cash welfare. As a result, the share of children with public health insurance increased by 10 percentage points during the mid-1960s, while the share of adults with public insurance increased by 2 percentage points.

However, there was geographic variation in the magnitude of the insurance coverage increase. Due to state-specific differences in demographics and program funding, the proportion of residents who were eligible for cash welfare—and therefore Medicaid—differed across states. The researchers utilize the resulting geographic variation in the insurance expansion to evaluate the impact of insurance coverage on infant mortality during the flu pandemics. Focusing on counties that were severely affected due to air pollution and urbanization, their analysis asks whether excess infant mortality fell differentially in states with higher Medicaid eligibility compared to lower-eligibility states, in the 1968-69 flu season compared to the 1957-58 flu season.

Their study demonstrates that the urban infant mortality disadvantage during pandemics was eliminated for residents of high-eligibility states during the 1968-69 flu season. Similarly, the deleterious effects of air pollution on infant mortality during flu pandemics were fully offset by residence in a high-eligibility state during the later flu pandemic.

While Medicaid improved mortality outcomes for all infants, the benefits were higher for non-white infants, reflecting the higher proportion of non-white mothers who were eligible for Medicaid. In addition, the health benefits of Medicaid were concentrated among newborns in their first day of life. This finding suggests two potential channels for Medicaid’s effect on infant mortality: improved maternal health as well as better access to acute care after delivery.

The positive health effects also spread beyond those who gained coverage. The implied magnitudes of the reductions in infant mortality from Medicaid are quite large: approximately 1.4 fewer infant deaths per 1,000 live births in the severely affected counties, or a 6 percent decline. The researchers conclude that these benefits are too large to have accrued only to newly insured households. Therefore, they infer that Medicaid reduced transmission of the flu during the 1968-69 flu pandemic and, consequently, provided health benefits even for households that were not enrolled in Medicaid.

The authors acknowledge financial support from the National Science Foundation grant SES-1627432, the Carnegie Mellon Electricity Industry Center (CEIC), Heinz College, the Berkman Fund, and from the Université de Montréal.