How Episode-Based Payment Affects Health Care Spending

Concerns over high health care spending in the U.S. have created significant interest in reforms that have the potential to lower expenditures. Changes in the structure of payments to health care providers — and more specifically, greater use of population or episode-based payments — are often proposed in this context.

Using episode-based payment (EBP), a spending target is set for an entire episode of care and the primary provider bears part or all of the risk of expenditure beyond this amount. The spending target covers payments to the primary provider and to all other providers involved in the episode. In contrast with fee-for-service (FFS) reimbursement, EBP creates incentives for the primary provider not only to use their own services efficiently, but also to manage the use of other health care services that have traditionally been reimbursed separately.

Despite strong interest in EBP, relatively little is known about how physicians respond to this payment system. The few existing studies of EBP are typically based on small demonstration projects with voluntary physician participation, and thus may not reflect the effects of a large-scale, mandatory EBP system.

In Effects of Episode-Based Payment on Health Care Spending and Utilization: Evidence from Perinatal Care in Arkansas (NBER Working Paper No. 23926) Caitlin Carroll, Michael Chernew, A. Mark Fendrick, Joe Thompson, and Sherri Rose explore the effects of the first large-scale EBP program that is mandatory for providers.

The context for the study is the Arkansas Health Care Payment Improvement Initiative (APII), a state-wide, multi-payer program with mandatory provider participation that was implemented in 2013. The APII initially covered five types of health care episodes, including perinatal care. Like many modern EBP programs, the APII employs a retrospective payment model, where providers are paid FFS while they oversee episodes, but face reconciliation payments at the end of the year. The provider's annual average spending per episode (adjusted for patient risk factors) is calculated based on episodes for which they served as Principal Accountable Provider (PAP). Each PAP's average episode spending is then deemed to be either commendable, acceptable, or unacceptable based on pre-determined thresholds. PAPs with unacceptable ratings are responsible for half of the spending beyond the acceptable level, while those with commendable ratings can share in half of the savings.

The APII's perinatal care episodes offer an appealing context in which to study EBP for several reasons. First, because of its multi-payer nature and the requirement that providers participate, the APII program covers the vast majority of births in the state. Second, spending on perinatal care is substantial and features large variation in episode costs, offering the potential for sizeable savings. In addition, a perinatal episode typically involves care across a variety of clinical settings, so coordination across providers may be particularly important. The PAP, who is often an obstetrician, may be able to reduce spending by changing the intensity of services they provide (for example, performing fewer caesarean sections), making fewer referrals for outpatient services like laboratory work, or reducing facility spending (for example, by referring patients to lower-priced hospitals or decreasing the length of stay). Finally, the volume of perinatal episodes is linked to births and thus there is essentially no scope for physicians to increase the number of episodes in response to a new payment system.

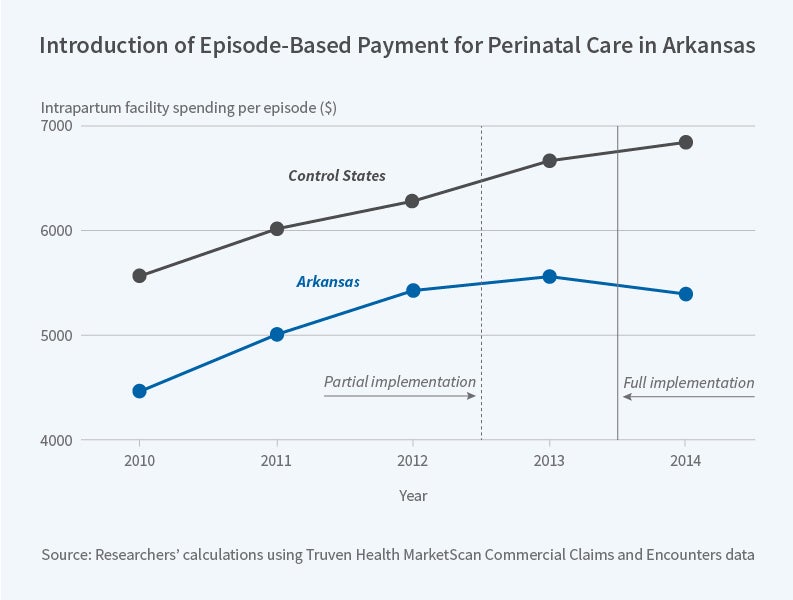

The researchers construct measures of spending per perinatal episode using claims data for a sample of enrollees in commercial health insurance plans and large self-insured firms. They use data from 2009 through 2014, spanning the period before and after EBP's introduction. As the data do not allow the tracking of spending by provider, the analysis focuses on the system-wide effects of implementing EBP, comparing trends in health spending in Arkansas to those in a group of control states in the South.

The researchers find that in the first full year of EBP implementation, spending per episode declined by 3.8 percent, or $403, in Arkansas relative to the control states. The savings were driven by slower spending growth in Arkansas after EBP implementation, while spending growth continued on a similar trajectory in the control states.

Over 80 percent of these savings stem from a large (6.6 percent) reduction in spending on inpatient facility care. The researchers find that this decline was largely driven by changes in the price of inpatient care rather than in the quantity of care. While unable to test directly for a mechanism underlying this effect, they suggest that a change in referral patterns is a likely cause. Outside of inpatient facility care, the implementation of EBP led to few changes in perinatal care. Declines in physician spending and outpatient spending were small and statistically insignificant, as were changes in utilization, including caesarean section rates and the length of inpatient stays. In terms of quality measures, EBP implementation was associated with improvements in chlamydia screening rates but no other changes.

The researchers conclude "our analysis suggests that EBP can be successful on a large scale" although the magnitude of the results also suggest that "system-wide bundled payment may have a modest impact compared to effects seen within smaller, voluntary programs." They note that modern EBP structures such as FFS with reconciliation provide different incentives than traditional, prospective EBP. Finally, they suggest that additional research that explores the effect of EBP in different clinical settings, that tracks behavior of providers over time, and that examines effects on patient outcomes would add to our understanding of the benefits and challenges of bundled payment reform.

The researchers acknowledge funding from the Laura and John Arnold Foundation, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality T32 trainee program (Carroll) and the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship (Carroll). Thompson wishes to disclose his involvement in developing the Arkansas Health Care Payment Improvement Initiative, both as Arkansas Surgeon General and as President of the Arkansas Center for Health Improvement. At least one researcher has disclosed a financial relationship of potential relevance for this research. Further information is available at:

www.nber.org/papers/w23926.ack.