Do Smoking Bans Affect Infant and Child Health?

Smoking has long been known to generate negative health effects for non-smokers through exposure to secondhand smoke, or environmental tobacco smoke (ETS). Infants born to women who smoke during pregnancy tend to have lower birthweight and are at higher risk for sudden infant death syndrome. In children, ETS exacerbates asthma and is linked to respiratory tract infections and other respiratory symptoms.

The costs of ETS are a key motivation for public policies that aim to curb smoking, such as cigarette taxes and anti-smoking educational campaigns. Bans on smoking in public places are another potentially potent tool. "100-percent smoke free" laws (SFLs) outlaw smoking anywhere on the premises and typically apply to restaurants, bars, and private workplaces. Currently, about three-quarters of the U.S. population is protected by a SFL at work and two-thirds is protected at bars and restaurants.

While past studies have established the health benefits of smoking bans for adults, there is little evidence regarding their impact on infants and children. If smokers compensate for public bans by smoking more at home, these laws could negatively impact child health. Conversely, if bans encourage smokers to quit or to smoke less at home, there could be health benefits for children.

Researchers Kerry Anne McGeary, Dhaval Dave, Brandy Lipton, and Timothy Roeper take up this question in their paper Impact of Comprehensive Smoking Bans on the Health of Infants and Children (NBER Working Paper No. 23995).

The researchers obtain data on infant health outcomes from the Vital Statistics census of births and child health data from the National Health Interview Survey. These data are combined with comprehensive information on state and local SFLs for the period 1990 to 2012 in order to test whether the implementation of a SFL in a given state or locality is associated with a change in infant and child health.

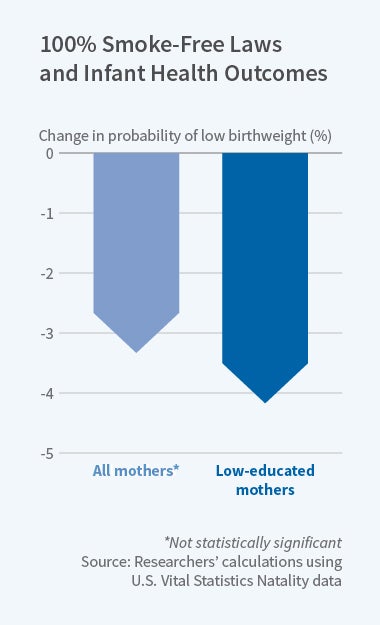

The researchers find that mothers living in areas protected by comprehensive 100% SFLs that apply in workplaces, restaurants, and bars have a 3.3 percent associated decline in the probability that an infant is born with low birth weight, although the effect is not statistically significant. The effect of the law is stronger for babies born to mothers with at most a high school education — for this group, the law's effect is 4.2 percent and is statistically significant. Less educated mothers are three times as likely to smoke during pregnancy than mothers with more education and are more likely to live in neighborhoods with higher prevalence of smoking in general, exposing them to higher levels of ETS.

The effects of SFLs on infant health are only slightly reduced when the researchers control for the mother's own smoking during pregnancy, suggesting that the law's effect is primarily due to reduced exposure to ETS rather than to changes in maternal smoking. The authors also report that the results are larger for married mothers, suggesting that the law may lead to reduced smoking by husbands.

Turning to child health, the researchers find that 100% SFLs are associated with reductions in respiratory allergies, asthma attacks, ear infections, emergency room visits, and reports of poor health. The effects are larger among children with less educated mothers and children diagnosed with asthma. Finally, the researchers show that SFLs are associated with decreases in smoking in the home for current smokers, especially those with less education, confirming that this is an important mechanism for the law's effects.

Overall, this study indicates that the health benefits of smoking restrictions extend to infants and children, particularly those in low-educated households. The effects of SFLs are largest when the restrictions apply simultaneously to workplaces, bars, and restaurants within a locality and when they do not have any exemptions, such as allowing a designated area for smoking.

The researchers note that currently only 58 percent of the population lives in a locality with such comprehensive bans, suggesting that there is still considerable room for such restrictions to be enacted, generating positive spillovers onto infant and child health. Further, given the strong effects of these bans for children in low-educated households, "cumulative smoking restrictions may play a role in flattening the socioeconomic gradient in infant and child health."

This research is supported by a grant from the National Cancer Institute (1R21CA167578-01).