Does Better Health Reduce Domestic Violence and Illicit Drug Use?

Domestic violence is a significant social problem in the U.S., with 4.5 million instances of domestic abuse annually and over one in five women experiencing physical assault by an intimate partner at least once in her life.

Past research has established the dual relationship between education, employment, and abuse, whereby low education and poor labor market prospects raise the risk of domestic violence while abuse also undermines educational attainment and employment. Less well understood, however, is whether there are similar ties between health and domestic violence. Poor health and chronic illness may leave an individual more vulnerable to abuse, and violence, by its very nature, poses a risk to health.

In Health, Human Capital and Domestic Violence (NBER Working Paper No. 22887), researchers Nicholas Papageorge, Gwyn Pauley, Mardge Cohen, Tracey Wilson, Barton Hamilton, and Robert Pollak explore the effect of health improvements on domestic violence.

Estimating a causal effect of health on domestic violence is made more challenging by the possibility that abuse may also affect health. Alternatively, omitted third factors could affect both health and violence. To overcome these difficulties, the researchers focus on whether an unexpected change in health due to a medical breakthrough is associated with a change in violence. Specifically, they look at how the introduction of highly active antiretroviral treatment (HAART) for women infected with HIV affected their exposure to violence and illicit drug use.

The researchers use data from the Women's Interagency HIV Study, a unique dataset that includes HIV-positive and HIV-negative women with similar levels of risky behavior. The study began in 1994, prior to the widespread introduction of HAART in 1996, and followed women over time. The researchers compare domestic violence and illicit drug use before and after the introduction of HAART for chronically ill HIV-positive women, who stood to benefit from the new treatment; healthy HIV-positive women and HIV-negative women serve as control groups to capture any changes over time in violence or drug use that are unrelated to the new health technology.

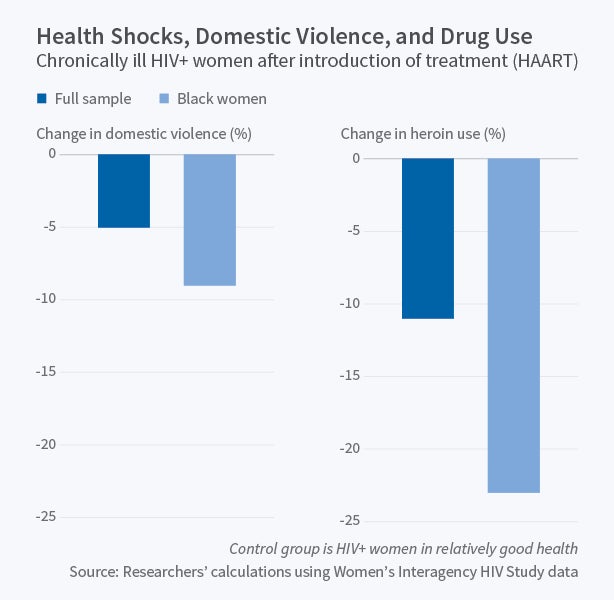

The introduction of HAART is estimated to reduce domestic violence by 5 percent for chronically ill HIV-positive women. The effect for black women is even larger, 9 percent. To provide a sense of the magnitude of these effects, the researchers note that another study found that the decline in the male-female wage gap that occurred over two decades reduced domestic violence by 9 percent. The researchers also use their empirical approach to explore the effect of HAART on illicit drug use. They find that its introduction reduced heroin use by 11 percent for the full sample of chronically ill HIV-positive women and by 23 percent for black women in the sample.

In explaining their results, the researchers suggest that health may affect domestic violence through the channel of human capital. Economists have long viewed health as a form of human capital. Higher levels of human capital may enable women to leave abusive partners by providing better outside options. Women with more human capital also face stronger incentives to avoid risky behaviors with future negative consequences, such as illicit drug use.

The researchers note "our empirical results illustrate the far-reaching implications of medical innovation." They conclude, "our findings also suggest that policies that enhance women's human capital, such as access to better healthcare technology, can affect some of the most frustratingly persistent social problems."

At least one co-author has disclosed a financial relationship of possible relevance for this research. Further information is available online at: http://www.nber.org/papers/w22887.ack.