Surprise Charges for Emergency Care

Patients who visit a hospital in their insurer's network may be surprised to receive a bill for services from an out-of-network provider who treated them during their stay. This surprise is particularly troubling when the visit is to the emergency department (ED), since patients in the ED are in medical distress and not in a position to choose their provider.

Hospitals and physicians negotiate contracts separately with insurers, so a hospital in the patient's network may be staffed by physicians that do not have a contract with the patient's insurer. Physician charges on out-of-network bills are not set through a competitive process and may be significantly higher than in-network or Medicare rates for the same services. When a patient receives an out-of-network bill, their insurer may choose to reimburse the billed amount, though the patient may still face substantial cost sharing. Alternatively, the insurer may pay the physician only the usual and customary rate, leaving the physician free to "balance bill" the patient for the remainder of the charge, or may not reimburse at all. In any case, the patient can be liable for a large bill.

In Surprise! Out-of-Network Billing for Emergency Care in the United States (NBER Working Paper No. 23623), researchers Zack Cooper, Fiona Scott Morton, and Nathan Shekita explore the scope of this phenomenon and analyze the effect of a New York state law designed to protect consumers from surprise bills.

Over the past several decades, ED care has accounted for a growing share of hospitals' inpatient admissions. There has been rapid growth in the share of hospitals that outsource the management, staffing, and billing of their EDs in an attempt to run these important departments more efficiently. At present, 65 percent of the physician ED workforce is outsourced, with two firms — EmCare and TeamHealth — collectively accounting for 30 percent of the outsourced physician market.

For the analysis, the researchers use claims data from a large commercial insurer to construct a sample of 9 million ED visits over the period 2011-15, representing $28 billion in spending. The data include the ED physician charge, the amount reimbursed by the insurer, and the amount paid by the patient as a copayment or towards their deductible; The data do not capture other patient payments made in response to balance billing. The researchers mine publicly available data to identify the hospitals in their sample that have contracts with EmCare and TeamHealth.

The researchers find that 22 percent of patients visiting an in-network hospital are treated and billed by an out-of-network provider, but the mean doesn't tell the whole story. The share of patients receiving an out-of-network bill varies significantly across hospitals — in the 15 percent of hospitals where such billing is most common, over 80 percent of patients receive an out-of-network bill. Nearly half of ED patients in Texas receive an out-of-network bill, as do a third of patients in many Southern states. The average out-of-network physician charge is $786, more than six times the Medicare payment for these services. The average physician payment from the insurer and patient cost-sharing is $327, leaving patients facing an average potential balance bill of $448.

The practice of out-of-network billing is more common at for-profit hospitals and hospitals that outsource their ED services to EmCare. This leads the researchers to evaluate how practices change when a physician-outsourcing firm takes over the management of the ED. Following the entry of EmCare, out-of-network billing rates increase by 81 to 90 percentage points and physician services are 43 percent more likely to be coded using the most high-intensity, high-paying code. EmCare's entry also results in increases in the use of imaging services and inpatient admits from the ED to the hospital. This pattern is consistent with hospitals incurring a reputational cost from out-of-network billing and receiving a transfer from physicians — in the form of higher fees from imaging, for example — to compensate them.

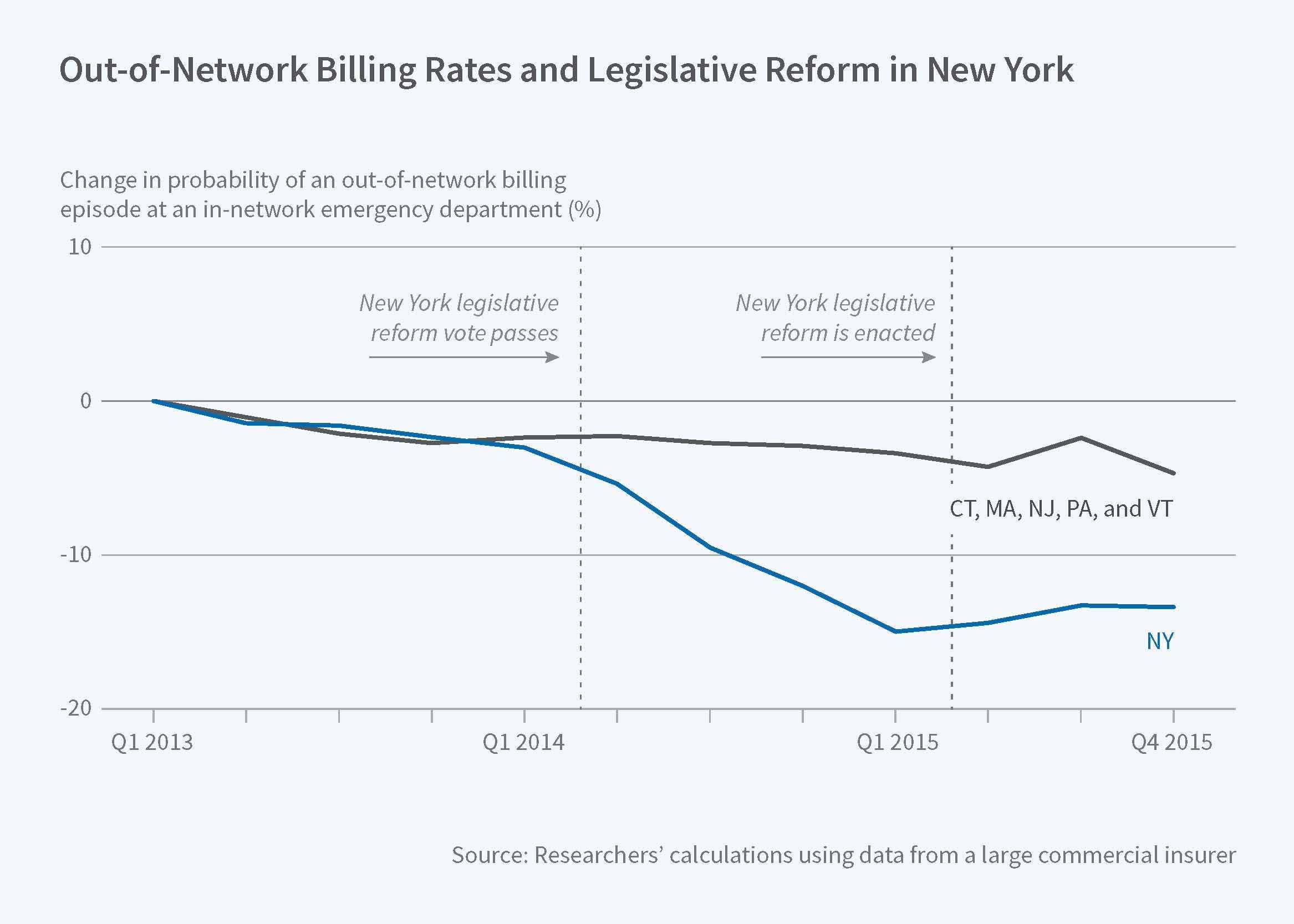

Finally, the researchers examine the impact of an innovative 2014 New York state law, which banned the practice of balance billing and required insurers and physicians to use binding arbitration to settle disputed bills. Following the law's passage, the out-of-network billing rate fell by substantially more in New York than in other nearby states. However, the law's protection is incomplete because it does not apply to insurance plans that are exempt from state regulation (about half of all privately insured patients are enrolled in such plans) and also does not ensure that physician ED charges are competitively set.

Indeed, as the researchers explain, the fundamental problem is that there is a missing contract between physicians and insurers. Some states have tried to address this by setting a regulated payment rate, although this does not restore a competitively set price to the market. The researchers note that "an alternative policy approach would be for states to require hospitals to sell an ED service package that includes both physician and facility services. In a state with this type of packaged payment, hospitals would negotiate ED payment rates with insurers and reach competitively set prices that reflect the cost of both the physician and the facility. Under this alternative policy, a patient using an in-network ED would be treated by in-network physicians. Further, this alternative policy would promote competition at all levels of the health system. Crucially, under this type of alternative policy, privately insured patients accessing EDs in emergencies would also be fully protected from surprise bills."

The researchers acknowledge funding from the National Institute for Health Care Management Foundation.