Can Policy Interventions Reduce Evictions?

In a typical year, about 5 percent of tenants have an eviction case filed against them. In Nonpayment and Eviction in the Rental Housing Market (NBER Working Paper 33155), John Eric Humphries, Scott T. Nelson, Dam Linh Nguyen, Winnie van Dijk, and Daniel C. Waldinger analyze lease-level landlord records to determine what leads to an eviction decision and how various policies might affect the eviction rate. They examine the payment and eviction histories of nearly 6,000 tenants between 2015 and 2019, which they describe as reflecting professionally managed rental properties in low-income neighborhoods of US urban areas.

Rental assistance and legal aid delay or prevent some evictions, but have modest overall effects.

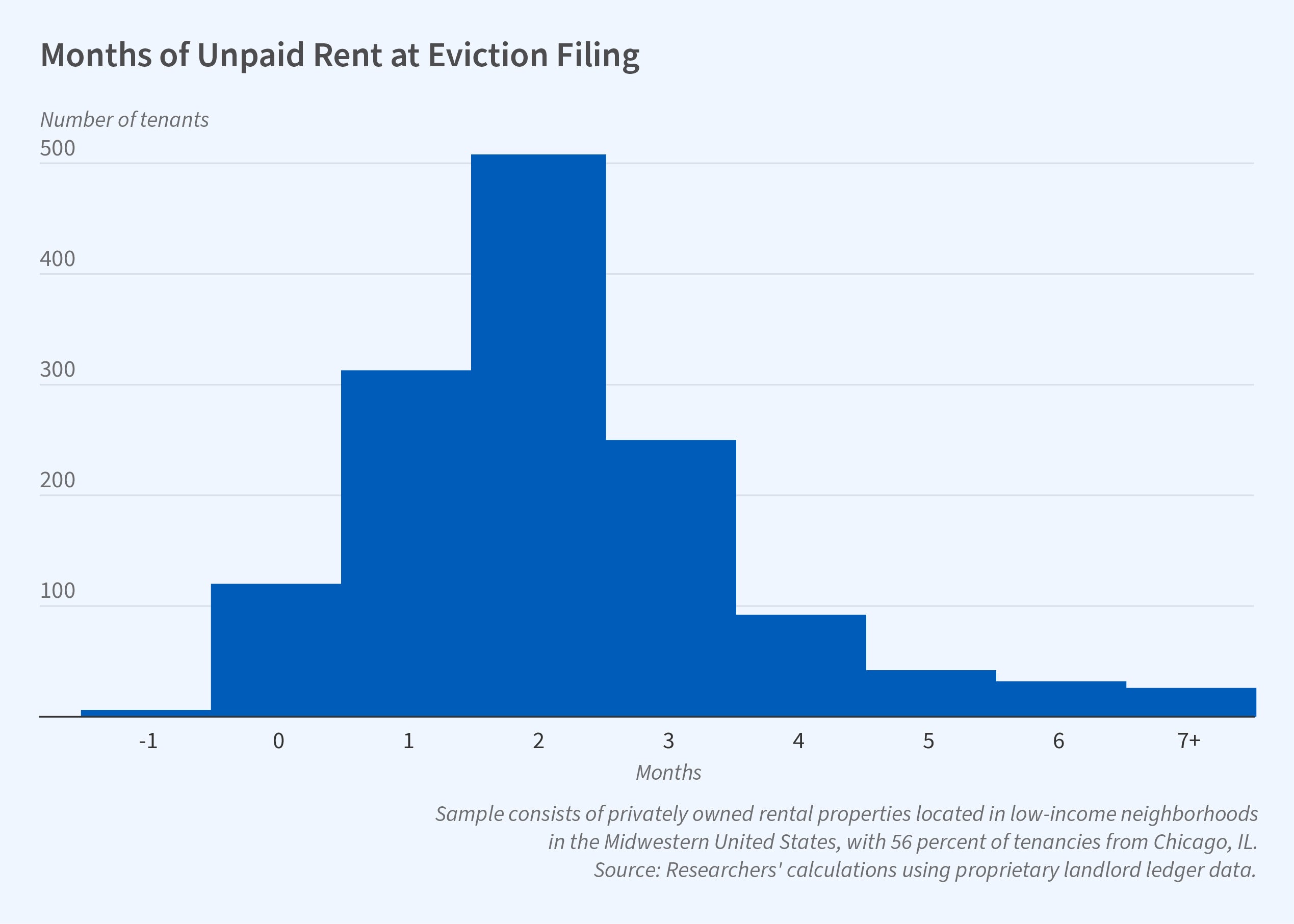

In their data sample, nonpayment and eviction were common — more than 30 percent of tenants were at least two months behind on rent at the end of their tenancies, and nearly one in four tenants were evicted. However, landlords often tolerated some nonpayment and typically waited until a tenant had missed multiple payments to file for eviction. This suggests that landlords wait for uncertainty to resolve about whether the tenant would catch up. Indeed, almost half of the tenants in the sample fell behind on their rent at some point, but 39 percent of this group — or about 20 percent of the tenants analyzed — eventually resumed paying and repaid all the overdue rent.

Based on these patterns, the researchers estimate a dynamic discrete choice model of a landlord’s decision to evict their tenant. Landlords behave as though it costs them between two and three months of rent to initiate an eviction proceeding. The authors also estimate that while many tenants recover from default, evicted tenants are less likely to. Only 15 percent of evicted tenants would have paid at least 10 of the next 12 months of rent if the landlord had not evicted them.

The researchers model three types of interventions for averting eviction: taxing landlords for filing an eviction, delaying the eviction process through legal means, and providing short-term rental assistance. They calibrate each of these interventions to generate what they estimate would be a 5 percent reduction in the eviction rate.

The three policies differ substantially in the types of evictions prevented and the costs to landlords and taxpayers. A simulated eviction tax would result in tenants whose evictions are delayed or prevented staying a median of seven additional months in their rental units. The researchers calculate that of those whose evictions are delayed or prevented, 22 percent would have been able to pay at least 10 of their next 12 months of rent had they not been evicted. In contrast, in a simulation where legal aid slows the eviction process, the median tenant whose eviction is delayed would stay four additional months, and only 12 percent of these tenants would have paid at least 10 of the next 12 months had they stayed. The legal aid option is particularly costly to landlords because it benefits the tenants least likely to pay. The third option, short-term rental assistance, results in outcomes for both landlords and tenants that fall between those for the tax and legal aid.

The researchers conclude that general policies with moderate costs to landlords and taxpayers “are unlikely to prevent the majority of evictions,” but they point out that policies precisely targeted to renters with a high likelihood of resuming payment in the future might be cost-effective.

— Steve Maas

This research is funded in part by the Industrial Organization Initiative at the Becker Friedman Institute at the University of Chicago and by the Fama-Miller Center for Research in Finance at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business.