The Effect of Pollution on Worker Productivity

Among call center workers in two Chinese cities, each 10-unit increase in the pollution index reduced worker productivity—measured by number of calls handled—by 0.35 percent.

Even in a job where employees only physical exertion involves answering the phone, air pollution takes its toll on productivity.

That is the finding of The Effect of Pollution on Worker Productivity: Evidence from Call-Center Workers in China (NBER Working Paper 22328) by Tom Chang, Joshua Graff Zivin, Tal Gross, and Matthew Neidell. While previous studies have shown that pollution affects productivity in physically arduous jobs, the new research gauges its effects on workers whose tasks are primarily cognitive.

Ctrip, China's largest travel agency, provided data on the daily productivity of 5,000 workers at its call centers in Shanghai and Nantong, which was measured against the government-reported daily air pollution index (API) for each city.

The primary pollutant in both cities is particulate matter, largely the result of fossil fuel combustion. The smallest of these particles are so fine that they can penetrate indoors and be absorbed into the bloodstream, potentially affecting brain function. Particulate exposure also irritates the ears, nose, throat, and lungs, and causes mild headaches, which might similarly impede work performance. For particularly sensitive individuals, symptoms occur when the index rises above 100. Symptoms become more widespread when the index exceeds 150. To place this pollution level in perspective, in 2014, the API exceeded 150 on 13 days in Los Angeles and 33 days in Phoenix.

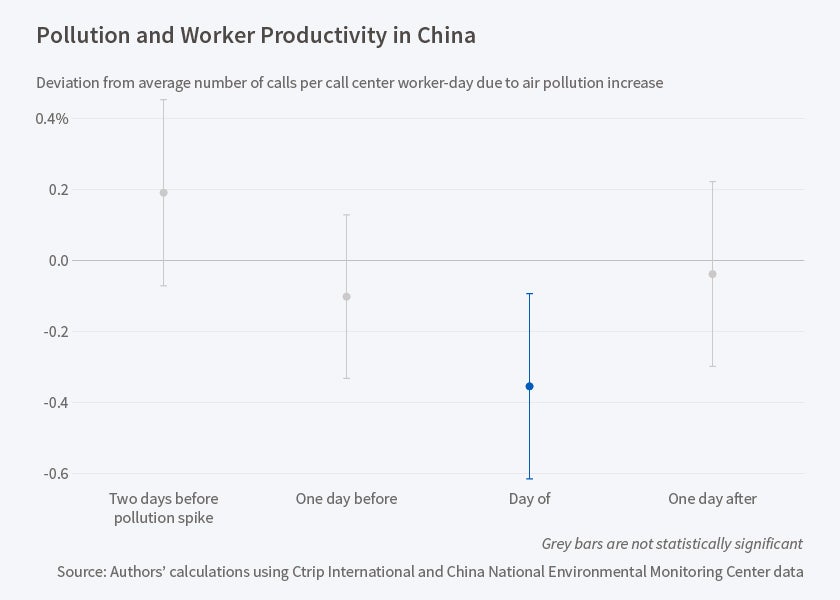

The study of Chinese workers found that for each 10-unit increase in the pollution index, worker productivity, measured by number of calls handled, declined by 0.35 percent. The average duration of individual calls was not affected by pollution levels, but the time workers spent on break increased. Poor air quality impeded the performance of otherwise highly productive employees as much as it did that of less productive workers.

One concern the researchers had was that traffic—a major contributor to pollution—would distort the results of their study. A nightmare commute could reduce productivity by raising employee stress and causing late arrivals to work. However, the company was piloting a work-at-home program for 150 employees during part of the study period, and their performance was similarly affected by pollution.

The researchers illustrate the magnitude of their findings by assuming that the same relationship that they estimate in China would apply to workers in Los Angeles County. They estimate that on the 90 days in 2014 when particulate pollution levels exceeded federal standards, productivity in the service sector was reduced by $374 million relative to what it would have been if the pollution levels had just met the federal standards.

"Given the size of the service and knowledge sectors in the developed world, even very small impacts from pollution could aggregate to rather substantial economic damages," the researchers conclude. "If our measured productivity impacts are the result of diminished cognitive function, the negative impacts of pollution may well be larger for high-skilled occupations that form the backbone of the service and information economy."

—Steve Maas