Long-Term US Treasury Bonds Have Lost Their 'Specialness'

An investor preference that for decades reduced borrowing costs for the U.S. government has disappeared since the global financial crisis.

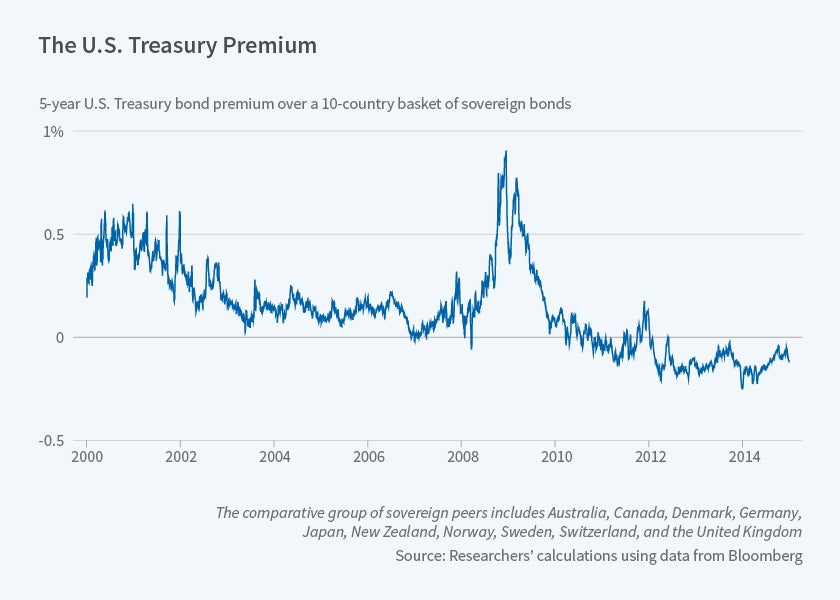

Investors have traditionally preferred U.S. Treasury bonds over the government bonds of other nearly default-free nations, a "specialness" that has reduced borrowing costs for the U.S. federal government. But that advantage has disappeared since the global financial crisis, at least for medium- and long-term U.S. government bonds, according to new research.

Researchers Wenxin Du, Joanne Im, and Jesse Schreger build on what's known as the "convenience yield" of U.S. Treasuries — the return that investors forgo by holding U.S. government debt rather than U.S. corporate or other private debt. They calculate a similar measure of the difference between the yield on U.S. Treasury bonds and the average implied dollar yield paid by 10 near-default-free sovereigns. They call this spread the "U.S. Treasury premium." The 10 nations (Australia, Canada, Denmark, Germany, Japan, New Zealand, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom) have traditionally paid more than the United States to borrow, even though all of them, except for Japan, have AAA or near-AAA sovereign credit ratings.

Before the crisis, the yield on Treasuries with a five-year maturity was 21 basis points lower than the FX-swap implied dollar yield paid by foreign governments. Since the crisis, this gap has narrowed and even reversed sign. On average, Treasury yields have been higher by 8 basis points, according to the research reported in The U.S. Treasury Premium (NBER Working Paper No. 23759).

"[T]he decline in the [specialness of U.S. Treasuries] cannot be explained away by credit risk or FX swap market mispricings," the researchers write. "In contrast, short-term U.S. Treasury bills have retained their specialness after the Great Financial Crisis." During 2007-09, the premium for three-month Treasuries shot up to 280 basis points while the average five-year premium increased 90 basis points. In the 2010-16 post-crisis period, three-month Treasuries returned to their 20-point pre-crisis average. However, the premium or specialness of medium- and long-term U.S. Treasuries steadily declined, until it disappeared.

The researchers consider three factors that may contribute to the Treasury premium: the sovereign credit risk differential between the U.S. and other nations, swap market mispricings, and differences in liquidity broadly defined. Pre-crisis, the first two factors were negligible; the researchers conclude that liquidity mostly drove the Treasury premium. Post-crisis, liquidity played, if anything, an even larger role, at least for medium- and long-term Treasuries, because the other factors tended to increase the premium.

The U.S. Treasury premium rises when the U.S. debt-to-GDP ratio is low and Treasuries are scarce relative to foreign government bonds; in these circumstances investors are prepared to pay more in forgone yield for these bonds. While the researchers are cautious about interpreting this relationship, they say it does suggest that the higher the U.S. government debt, the smaller the premium on medium- and long-term bonds.

— Laurent Belsie