Hospitals as Insurers of Last Resort

Each newly uninsured person leads to nearly $900 in uncompensated care costs, of which hospitals absorb approximately two thirds as lost profits.

When patients can't or won't pay for hospital care, who picks up the tab?

During the debate over the Affordable Care Act, many proponents argued that hospitals made up for losses by charging other patients more, resulting in higher insurance premiums and co-pays. In Hospitals as Insurers of Last Resort (NBER Working Paper No. 21290), Craig Garthwaite, Tal Gross, and Matthew J. Notowidigdo calculate that hospitals pass along only one third of those costs by raising rates. As a result, they predict, the impact of the ACA on insurance premiums will be considerably less than anticipated.

The researchers analyze previously confidential, hospital-level financial data from 1984 through 2011. In addition, they study hospital finances in Tennessee and Missouri, which sharply reduced their Medicaid rolls in 2005 because of budget shortfalls. The national and state datasets yield similar results.

"We estimate that each newly uninsured person leads to nearly $900 in uncompensated care costs...that association is remarkably robust to state and year fixed effects, the inclusion of time-varying state economic controls, and region-by-year fixed effects." On average, they conclude, hospitals absorb approximately two-thirds of these costs through lost profits.

In 2012, uncompensated care cost U.S. hospitals more than $46 billion. Had hospitals been able to collect all of these bills, their profits would have been 70 percent higher. The researchers lump together the cost of caring for the uninsured with unpaid debts. Given the disparity between hospital list prices and payments negotiated with insurers, the researchers use a cost-to-charge ratio to approximate the actual cost of services. Federal law mandates that hospitals treat emergency patients regardless of whether they are covered by insurance. Moreover, more than half of all hospitals studied are nonprofit organizations that are exempt from federal, state, and local taxes. In return, they are expected to provide community benefits such as charity care.

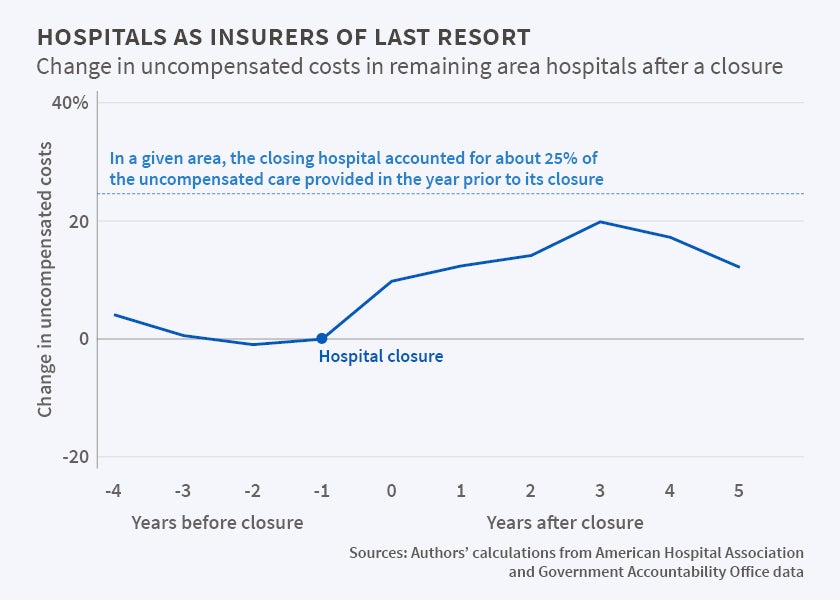

The researchers find that nonprofit hospitals care for a disproportionate number of the uninsured. For example, when a hospital closes, the authors find a significant increase in the number of uninsured patients at surrounding nonprofit hospitals, but little change at for-profit hospitals. The researchers caution that nonprofit hospitals may be more likely than for-profits to locate in areas with a high concentration of the uninsured. In addition, they suggest, for-profit hospitals may keep their costs lower than nonprofits by more closely managing services provided to uninsured patients.

The authors note that their findings are particularly relevant to the 21 states that as of May 2015 had chosen not to expand Medicaid coverage under the Affordable Care Act, leaving 5.2 million individuals ineligible. "We calculate that the money states will 'save' from not expanding Medicaid is less than the hospital uncompensated care costs generated by not expanding Medicaid."

In their conclusion, the researchers suggest that insurance protects not only patients but also health providers, particularly those located in low-income areas. Noting that Medicaid has escaped the cutbacks experienced by other welfare programs, such as food stamps, they observe that "Given that hospitals are an important political force at all levels of government, the factors requiring hospitals to provide uncompensated care may thus have unintentionally assured Medicaid's long-term political stability."

—Steve Maas