What Happens When Refugees Come to the United States

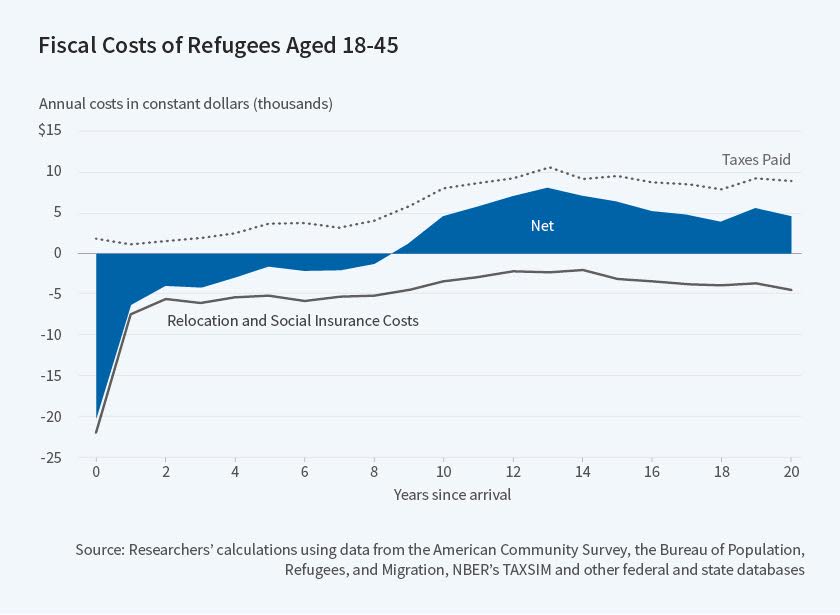

Over the first 20 years in the U.S., the average adult refugee pays taxes that exceed relocation costs and social benefits.

Are refugees a burden on the taxpayer? New evidence suggests that, with a long enough perspective, the answer is no. William N. Evans and Daniel Fitzgerald, in The Economic and Social Outcomes of Refugees in the United States: Evidence from the ACS (NBER Working Paper No. 23498), find that over their first 20 years in the United States, refugees who arrived as adults aged 18-45 contributed more in taxes than they received in relocation benefits and other public assistance. They also find that the younger the refugees were when they resettled in America, the more likely they were to catch up with their native-born peers educationally and economically.

The researchers constructed lifecycle profiles for refugees by extrapolating data from the 2010-14 American Community Survey. They separated refugees from other immigrants using Department of State data, and created a sample of 20,000 refugees who entered the country in 1990-2014. Their sample represents a third of refugees who arrived during the period. The researchers found that refugees who arrived before the age of 14 had, by ages 19-24, graduated from high school at the same rates as their U.S.-born counterparts. At ages 23-28, those refugees displayed the same college graduation rates as natives.

Refugees who arrived as older teens took longer to obtain their high school diplomas than their U.S.-born peers. The researchers attribute this largely to language difficulties and the fact that many in this demographic arrived as unaccompanied minors.

Initial disadvantages are offset by refugees' appetite for education, the researchers find, noting that "refugees who arrived as children of any age have much higher school enrollment rates than U.S.-born respondents of the same age." The gap in high school graduation rates observed between refugees and natives aged 19-24 disappears within a decade, and the gap in college graduation rates is halved over this period. Controlling for educational attainment, the researchers found "no difference in economic outcomes between refugees who arrived as children and U.S.-born survey respondents."

The researchers then turn to refugees who arrived as adults ages 18-45. On average, these individuals were less educated and less fluent in English than their U.S.-born counterparts. After six years in the United States, however, these individuals had higher labor-force participation and employment rates than similarly aged U.S. natives. Given their lower educational and language levels, their earnings were lower and their use of welfare and food assistance higher than the U.S.-born group. Education and language ability accounted for 60 percent of the earnings difference. Controlling for those factors, the researchers found that after a decade, public assistance rates were the same for refugees and the native born.

The researchers calculate on average, the U.S. spends $15,148 in relocation costs and $92,217 in social benefits over an adult refugee's first 20 years in the country. Over that same time period, the average adult refugee pays $128,689 in taxes — $21,324 more than the benefits received.

— Steve Maas