Organizational Barriers to Adoption of New Technology

An experiment in the production of soccer balls suggests that sharing production gains with workers helps firms embrace change.

Slow diffusion of promising new technology has long been the bane of inventors, innovators, company owners, and enterprising employees who recognize opportunities to improve productivity. In Organizational Barriers to Technology Adoption: Evidence from Soccer-ball Producers in Pakistan (NBER Working Paper No. 21417), David Atkin, Azam Chaudhry, Shamyla Chaudry, Amit K. Khandelwal, and Eric Verhoogen explore reasons for resistance to change.

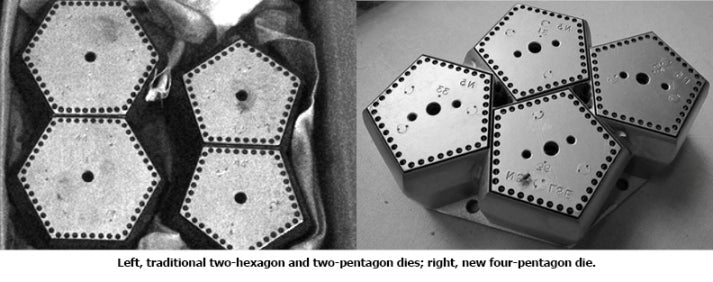

A traditional soccer ball has 20 hexagons and 12 pentagons cut from sheets of artificial leather known as rexine. A metal die and hydraulic press are used to cut the panels from laminated rexine sheets. In the course of their research on the soccer ball industry, Verhoogen and his wife, Annalisa Guzzini, an architect, discovered a new die design (based on a cutting pattern from a YouTube video of a Chinese factory) that allowed more pentagons to be cut from each rexine sheet, thus reducing waste and improving efficiency in the production process. The new technology was calculated to reduce production costs by 1 percentage point in an industry with an average profit margin of only 8 percentage points–an unambiguous benefit to ball-manufacturing companies.

The researchers introduced this new technology in Sialkot, Pakistan, where a cluster of some 135 soccer-ball manufacturers employs thousands of workers and makes about 30 million soccer balls per year, some of them for large global firms. They found that a majority of firms adopted the technology only after introduction of a pay-incentive program for workers. The clear benefits of the technology from the firm's perspective were not sufficient to ensure adoption.

In an initial experiment, the researchers randomly divided participating companies into three groups: those that would be given the new technology, those that would be given cash equivalent to the value of the new technology, and those that would be given nothing. After 15 months, they found the adoption rate of the technology was low in all three categories. After surveying employers and employees, they strongly suspected that a misalignment of payment incentives was at play, particularly among rexine cutters and printers, who traditionally were paid by the number of pieces they produce and who feared the slightly more time-consuming new technology might reduce their earnings. Anecdotal evidence suggested that some workers were actually misinforming employers about the productivity benefits of the new die.

In a second experiment, producers who had been given the new technology were divided randomly into two categories: those to which the researchers gave only reminders of the production benefits of the technology and those where the researchers implemented a new payment-incentive system in which workers received a lump-sum payment equal to a month's earnings if they demonstrated competence using the new technology.

Of the firms that implemented the new payment scheme and had not yet adopted the new die, a majority did adopt the new technology, while none of the firms that did not use the worker-payment system did so in the first six months, and only one did so in the first year. Though the sample size was small, the researchers were able to conclude that modest pay changes–small in comparison to the cost savings generated by the technology–had a significant impact on adoption and produced significant production benefits.

In follow-up surveys, the researchers found evidence suggesting that technology diffusion was slowed not only by workers' resistance, but also by employers' concerns about disrupting the explicit or implicit payment contracts already in place. Lack of knowledge about alternative payment systems also appears to have played a role in managers being hesitant to make changes.

"It seems likely that in order for technology adoption to be successful, employees need to have an expectation that they will share in the gains from adoption," the authors conclude. "[T]o the extent that firms must rely on the knowledge of shopfloor workers about the value of new technologies or how best to implement them, it appears to be important that some sort of credible gain-sharing mechanism be in place."

—Jay Fitzgerald