Informed Shoppers and Brand Premiums

Better-informed consumers are less likely to pay more for national brands.

Why are consumers willing to pay for a nationally advertised product when a store brand or generic of the same product may be had at one-third the price? In Do Pharmacists Buy Bayer? Informed Shoppers and the Brand Premium (NBER Working Paper No. 20295), Bart J. Bronnenberg, Jean-Pierre Dubé, Matthew Gentzkow, and Jesse M. Shapiro analyze wide-ranging shopper surveys and conclude that the answer lies in consumer information - and misinformation.

In a detailed case study of headache remedy purchases, the researchers find that more-informed consumers are less likely to pay extra to buy national brands, with pharmacists choosing them over store brands only 9 percent of the time, compared with 26 percent of the time for the average consumer. Similarly, chefs devote 12 percentage points less of their purchases of kitchen staples to national brands than otherwise similar non-chefs. The authors extend their analysis to cover 50 retail health categories and 241 food and drink categories and use the resulting estimates to develop a model of demand and pricing. They then quantify the degree to which brand premia result from misinformation, and determine how more accurate information would change the division of surplus among manufacturers, retailers, and consumers.

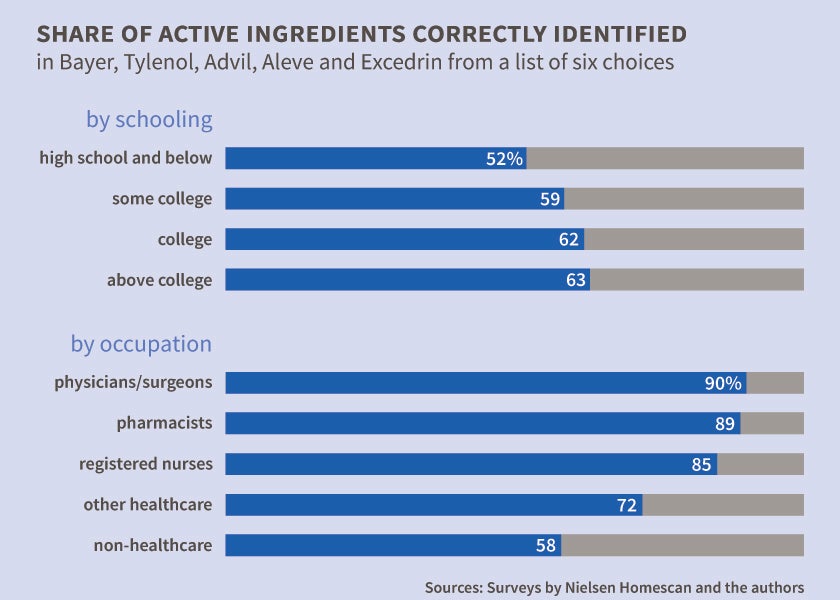

The study of headache remedies is based on a Nielsen Homescan database of purchases made on more than 77 million shopping trips by 125,114 households from 2004 to 2011. As indirect measures of information, the researchers use the shopper's occupation, educational attainment, and college major. The researchers also measure information directly through a survey of a subset of Nielsen panelists, in which panelists were asked to name the active ingredient in various national-brand headache remedies. They also asked respondents whether they agreed or disagreed with a series of statements, including "Store-brand products for headache remedy/pain relievers are just as safe as the brand name products."

Controlling for household income, other demographics, and the market, chain, and quarter in which the purchase is made, a household whose primary shopper correctly identifies all active ingredients in a national brand has an 85 percent chance of purchasing a store brand, 19 percentage points higher than a shopper who identifies none of the ingredients. All else equal, primary shoppers with a college degree are 4 percentage points more likely to purchase a store brand, and when the primary shopper works in a healthcare occupation other than pharmacist or physician, this is associated with an 8 percentage point increase in the likelihood of buying the store brand. When the primary shopper is either a pharmacist or a physician, the probability of purchasing the store brand is 91 percent, 15 percentage points higher than the probability of otherwise similar buyers who are not in these fields. Primary shoppers who were science majors in college buy more store brands than those with other college degrees.

In a second case study of pantry staples such as salt, sugar, and baking powder, the researchers find that chefs devote nearly 80 percent of their purchases to store brands, compared with 60 percent for the average consumer.

The authors argue that determining how much of the brand premium reflects misinformation has important implications for consumer welfare. They estimate that consumers spend $196 billion annually on consumer items in which a store-brand alternative to the national brand exists, and that they would save approximately $44 billion if they switched to the store brand. If consumers are systematically misled by advertising claims, say the analysts, this has clear implications for evaluating the welfare effects of the roughly $140 billion spent on advertising each year in the U.S., and for designing federal regulations to minimize the potential for harm.

-- Matt Nevisky