Tracking the Gifted Boosts High-Achieving Minorities

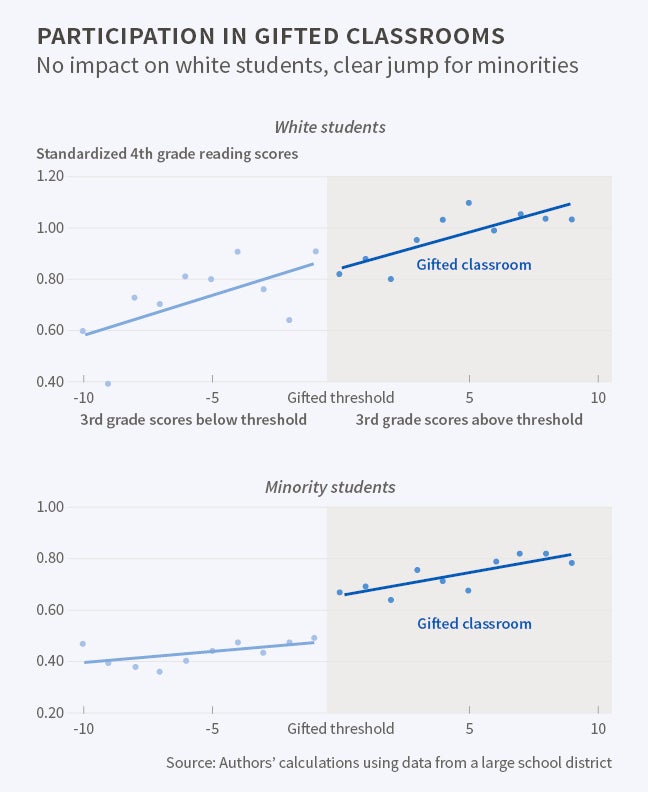

Participation in a fourth-grade class for the gifted raised reading and math scores of high-achieving black and Hispanic students, with little effect on whites.

For years, researchers have debated the impact of high-achievement classes on minority students. Are there significant gains for those who participate in special classes for gifted and high-achieving students? Do other students who are "left behind" in traditional classrooms experience a declining quality of education if gifted and high-achieving children are reassigned elsewhere?

In Can Tracking Raise the Test Scores of High-Ability Minority Students? (NBER Working Paper 22104), David Card and Laura Giuliano study the impact of tracking programs that place students—both truly gifted students with exceptionally high IQs and high achievers who don't fit the strict definition of "gifted"—in advanced fourth- and fifth-grade classes within a large urban school district. They conclude that high-achieving minority students make significant gains in such classes, and find no evidence of spillovers, good or bad, on students who remain in traditional classrooms.

Previous studies have shown that blacks and Hispanics are significantly underrepresented within high-achievement classes and that racial disparities widen even among high-achievers as time passes. In the new study, the researchers examine data from a large and racially diverse urban school district that, in 2004, implemented a policy requiring a school to create advanced academic classes for fourth and fifth graders if the school had one or more students who met the state's standards for gifted status (including a minimum IQ threshold of 130 points for non-disadvantaged students, or 116 points for subsidized lunch participants and English Language Learners).Because there usually were not enough such students to fill the classroom, schools were allowed to include high achievers in what became known as Gifted/High Achiever (GHA) classes. The GHA students were taught by many of the same teachers and used the same textbooks as students in traditional classes, but teachers were given some discretion over the pace and intensity of learning within GHA classrooms.

Using data compiled on third, fourth, and fifth graders in 140 elementary schools between 2008 and 2011, the researchers compared GHA and traditional classrooms. They found that participation in a fourth-grade GHA class had a significant positive impact on the test scores of high-achieving black and Hispanic students, who gained 0.5 standard deviation units in fourth grade reading and math scores. These effects extended into at least sixth grade. The effects for white students were small and insignificant.

The researchers did not find any evidence of either positive or negative spillover effects on other students in the same school or in other schools, including those who narrowly missed the cutoff for getting into GHA classes.

To investigate why there were impressive test-score gains among minority high-achieving students in GHA classes, while white high-achievers did not post similar results, the researchers explored a number of possible factors. They found that the quality of teachers and general positive peer effects within GHA classrooms accounted for only about 10 percent of the gains, and that other factors were at work, such as high teacher expectations and the lack of negative peer pressure in GHA classes. They conjecture that negative peer pressure about learning is more prevalent in traditional classrooms, causing many minority high-achievers to underperform within such settings.

"Overall, our results suggest that a comprehensive tracking program that establishes a separate classroom in every school for the top performing students has the potential to significantly boost the performance of higher achieving minority students—even in the poorest neighborhoods of a large urban school district," the researchers report.

—Jay Fitzgerald