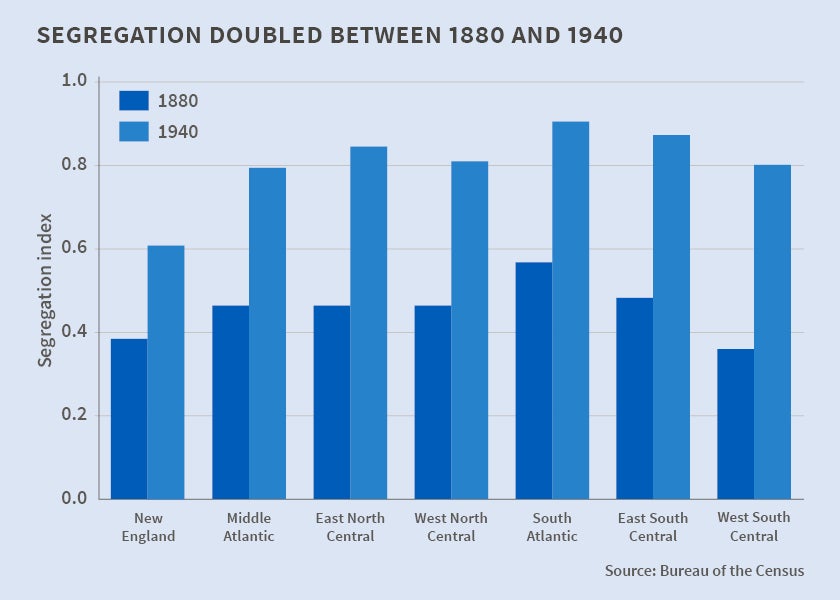

Residential Segregation in the U.S. Rose Dramatically, 1880-1940

The likelihood of having opposite-race neighbors declined precipitously in every region of the United States.

In The National Rise in Residential Segregation (NBER Working Paper No. 20934), Trevon Logan and John Parman introduce a first-of-its-kind measure of residential segregation based upon the racial similarity of next-door neighbors. Using the complete manuscript pages of the federal census to identify the races of next-door neighbors for the period 1880-1940, the authors were able to analyze segregation consistently and comprehensively for all areas in the United States, allowing for an in-depth view of the variation in segregation across time and space.

The authors find that residential segregation in the United States doubled from 1880 to 1940. The findings show that the likelihood of having opposite-race neighbors declined precipitously in every region of the United States. The rise in segregation occurred in areas with small black population shares, areas with large black population shares, areas that experienced net inflows of black residents, areas that experienced net outflows of black residents, urban areas with large populations, and rural areas with smaller populations. In light of these findings, the authors conclude that the traditional story of increasing segregation in urban areas in response to black migration to urban centers is incomplete, and must be augmented with a discussion of the increasing racial segregation of rural areas and other areas that lost black residents.

The findings complicate traditional explanations for increasing segregation as being due to blacks clustering in small areas abutting white communities, the use of restrictive covenants on residential housing, the presence of large manufacturing firms which employed blacks, and differences in transportation infrastructure, since these were all urban phenomena. The increase in rural segregation also complicates historical narratives that view population dynamics in rural areas as stagnant. The focus on urban segregation has neglected the fact that rural areas became increasingly segregated over time.

Logan and Parman suggest that because the rise in segregation over the first half of the 20th century was a truly national phenomenon, it opens new lines of inquiry. Understanding the relationship between segregation, urbanization, and population flows should help to explain the dynamics of segregation in cities and rural communities in the 20th century. These links have important implications for the skill mix of cities, public finance, education, inequality, health, and other measures of social wellbeing. The strong persistence of segregation that the authors find suggests that the roots of contemporary segregation may be more varied that previously thought. This gives rise to a range of questions about the impact of Jim Crow laws, racial violence, European immigration, internal migration, and the differences and similarities between racial segregation in rural and urban areas in the United States.

While this paper examines segregation patterns from the post-Civil War era to 1940, the authors' methodology could be applied to developing a better understanding of the modern impacts of segregation on a range of socioeconomic outcomes, the authors say, particularly segregation's effect on contemporary racial disparities.

-- Les Picker