Childhood Medicaid Coverage Improves Adult Earning and Health

Two studies use variation in Medicaid eligibility across birth cohorts and states to estimate the program's long-run effects on participants.

Medicaid today covers more Americans than any other public health insurance program. Introduced in 1965, its coverage was expanded substantially, particularly to low-income children, during the 1980s and the early 1990s.

Throughout Medicaid's history, there has been debate over whether the program improves health outcomes. Two new NBER studies exploit variation in children's eligibility for Medicaid, across birth cohorts and across states with different Medicaid programs, along with rich longitudinal data on health care utilization and earnings, to estimate the long-run effects of Medicaid eligibility on health, earnings, and transfer program participation.

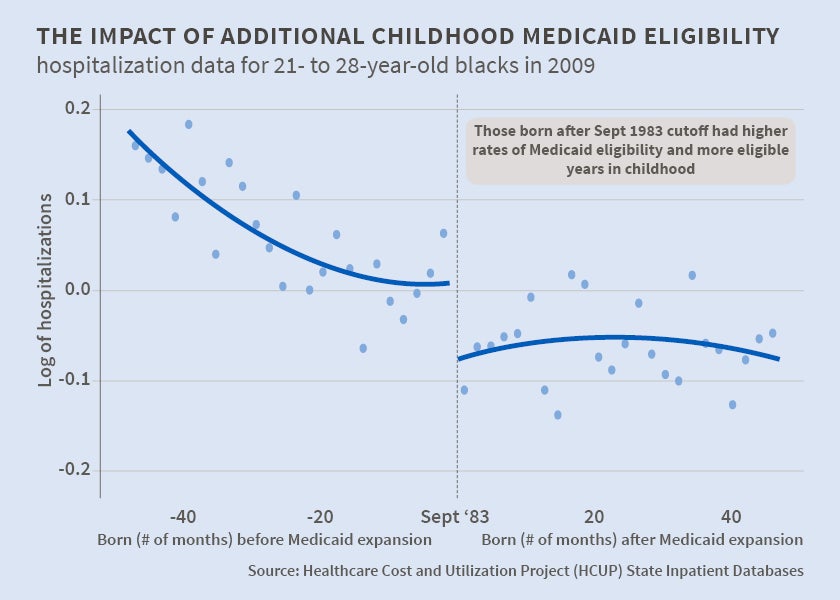

In Childhood Medicaid Coverage and Later Life Health Care Utilization (NBER Working Paper No. 20929), Laura R. Wherry, Sarah Miller, Robert Kaestner, and Bruce D. Meyer find that among individuals who grew up in low-income families, rates of hospitalizations and emergency department visits in adulthood are negatively related to the number of years of Medicaid eligibility in childhood. The authors exploit the fact that one of the substantial expansions of Medicaid eligibility applied only to children who were born after September 30, 1983. This resulted in a large discontinuity in the lifetime years of Medicaid eligibility for children born before and after this birthdate cutoff. Children in families with incomes between 75 and 100 percent of the poverty line experienced about 4.5 more years of Medicaid eligibility if they were born just after the September 1983 cutoff than if they were born just before, with the gain occurring between the ages of 8 and 14. The authors compare children who they estimate were in low-income families, and otherwise similar circumstances, who were born just before or just after this date, to determine how the number of years of childhood Medicaid eligibility is related to health in early adulthood. Their finding of reduced health care utilization among adults who had more years of childhood Medicaid eligibility is concentrated among African Americans, those with chronic illness conditions, and those living in low-income zip codes. The authors calculate that reduced health care utilization during one year in adulthood offsets between 3 and 5 percent of the costs of extending Medicaid coverage to a child.

In Medicaid as an Investment in Children: What is the Long-Term Impact on Tax Receipts? (NBER Working Paper No. 20835), David W. Brown, Amanda E. Kowalski, and Ithai Z. Lurie conclude that each additional year of childhood Medicaid eligibility increases cumulative federal tax payments by age 28 by $247 for women, and $127 for men. Their empirical strategy for evaluating the impact of Medicaid relies on variation in program eligibility during childhood that is associated with both birth cohort and state of residence. The authors study longitudinal data on actual tax payments until individuals are in their late 20s, and they extrapolate this information to make projections for these individuals at older ages. When they compare the incremental discounted value of lifetime tax payments with the cost of additional Medicaid coverage, they conclude that "the government will recoup 56 cents of each dollar spent on childhood Medicaid by the time these children reach age 60." This calculation is based on federal tax receipts alone, and does not consider state tax receipts or potential reductions in the use of transfer payments in adulthood.

Both studies use large databases of administrative records to analyze the long-term effects of Medicaid. The first study measures health utilization using the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) State Inpatient Databases for Arizona, Iowa, New York, Oregon, and Wisconsin in 1999, and those states plus Maryland and New Jersey in 2009. State hospital discharge data were also available from Texas and California. Data on all outpatient emergency department visits were available for six states in 2009. The second study examines data on federal tax payments and constructs longitudinal earnings histories for individuals who were born between 1981 and 1984. It also analyzes administrative records on Medicaid eligibility of children in this cohort.

-- Linda Gorman